Role-playing games offer participants limitless opportunities to explore new places, characters, and ideas. Do you want to be a vampire pirate? Cool! A cyberpunk android? All right! Do you want your game to take place in a medieval fantasy kingdom, a post-apocalyptic dystopian wasteland, or even other galaxies? No problem! With imagination the only barrier for what can be created, there should be a vast field of narratives told through games. Yet, role-playing games are often more narrowly defined.

Role-playing games have an established history of leaving setting and characters a blank slate, while often loosely drawing inspiration from Western themes. For example, when I was a kid and I played Dungeons and Dragons with my friends, we came in with unexamined expectations—the city we saved was always filled with white people, the mayor of the town was always a man, the kingdom was always vaguely built around an imagined medieval Europe. As an adult, I still see these elements and themes repeated in games today.

This is a common pitfall that minority advocates in gaming have come to call “defaultism.”

Defaultism is the idea that we fall back on the status quo when something is not defined. We go with what is most familiar and “normal.” White Americans are a little over two-thirds of the population, but the vast majority of our media is dominated by this demographic, not just in games, but movies, TVs shows, and books. Because of the primacy of white characters in media, if a character is not explicitly stated to be of a different race they are often assumed to be white. Similar problems arise with gender expectations and sexual orientation. Women are commonly typecast as secondary characters, like the love interest, or the victim, while queer characters are rarely seen, or used only as comic relief. Most gamers unconsciously gravitate to the straight white male as our hero, our role model, and the baseline for play.

When defaultism is the norm, vast groups of people and entire cultures are left unexplored and unused in games. These are lost opportunities to engage our imagination, to roam in rich, fertile and vibrant territory. Simultaneously, lack of representation makes the role-playing hobby harder to access for minorities. Without seeing themselves in these stories, why would they participate? The answer is that many times they don’t. I know that in my case, I was pulled in at a very young age. I may have turned away from role-playing games if I had come to them as an adult.

Specifically employing minority settings in RPGs is an easy and direct way to punch through defaultism. Changing the setting alters the cultural foundations of the world on which everything else is built, causing a fundamental shift and opening up access to viewpoints and stories that rarely get told. This can deeply enrich the storytelling while also making the game accessible to a wider audience, signaling to underrepresented groups that the narratives that speak to them are part of the fabric of the game. It’s a win-win.

For example, I am writing for a tabletop RPG called Dead Scare (a pun on “red scare”)—it’s a game about 1950s housewives fighting off zombies after the Soviets dump biological weapons on suburban America. The game takes a step away from the default right away, because it focuses specifically on women and their children surviving and fighting on their own merit and skill in an era where both were disempowered by society and largely voiceless outside the home. Women in the United States were not even able to apply for a credit card without their husband’s approval until 1974!

The creator of Dead Scare, Elsa Henry, contacted a handful of designers to create setting snapshots for her game called “Postcards from Across America.” She was looking for untold stories and I decided to write about Tulsa, and focus specifically on the Greenwood District. Once called Black Wall Street, Greenwood was a thriving community in north Tulsa that created unprecedented prosperity for itself in a time when Blacks all over the country still struggled against Jim Crow laws, overt threats and lynching from racist groups like the KKK, and extreme systemic oppression. The neighborhood boomed with businesses, hospitals, and even a number of privately owned bi-planes. It was an amazing and inspiring community. It wouldn’t last, though.

In 1921 there was a race riot that tore Greenwood down to its very foundations. White people invaded the district, looted, burned, murdered, and even stole the planes and bombed the neighborhood from the air. It’s estimated that hundreds died, and thousands more black people were arrested and held in camps for simply existing in the area while white people were trying to kill them.

Greenwood never recovered. Not ever. When people tried to rebuild they found that insurance schemes made it impossible. When they tried to open their businesses back up they were stymied at every turn. To add insult to injury, the events of the race riot were blacked out from local and state history. Newspaper articles about it went missing from archives. It was not taught about at the local schools. It was purposely forgotten. I attended university and worked in Tulsa and saw first-hand the lasting impact of the riots on its people.

Greenwood in the 1950s was still struggling to recover from the race riot, and still retained some margin of hope. Both the ghosts of prosperity and ruination clamored within living memory. What must it have been like for a woman, a community member in Greenwood, to live her life there? To remember how things used to be, so promising, so golden, and then having to live with the bitter ashes of the present? How would a person informed by this reality deal with the events of a red scare come true? What kind of story would unfold? Certainly, her experiences would be dramatically different than that of her middle-class white counterpart living just a few miles away with her picket fence and chrome toaster.

It’s a compelling narrative, and as it turns out, the Tulsa race riot is something a lot of people still haven’t heard of before, despite it being the single worst incident of racial violence in American history. And here is the other point to working minority settings into the gaming experience: they are a way to unearth the hidden past and bring to light stories that are powerful and moving, but willfully forgotten or minimized by the majority. Engaging with these people and places builds empathy, understanding, and context for lived experiences that need to be brought into the mainstream, recognized, and understood.

Exploring the history of Greenwood through games struck a chord with others. James Mendez Hodes, who is developing a game called AfroFuture with the assistance of Different Play, asked me to work with him on a Greenwood setting for his game. Jaydot Sloan of Vanity Games made a Steal This Character profile for Dead Scare which featured a young black girl named Harriet Smythe.

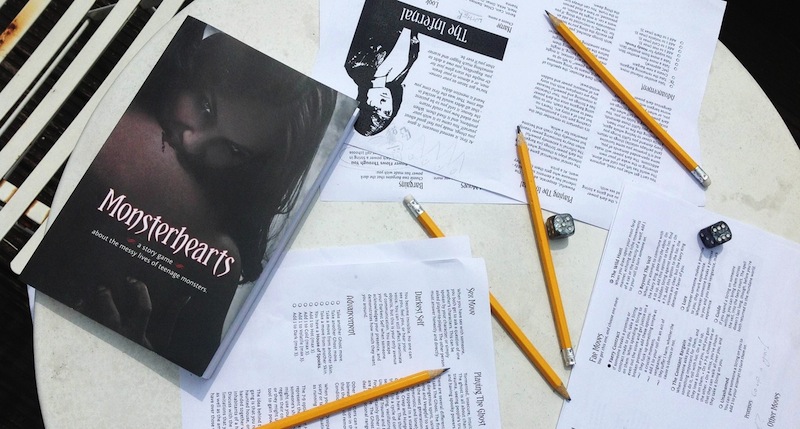

The excitement over minority settings does not begin and end with a single piece, however. Jason Morningstar’s recently released game Night Witches, which is explicitly about female bomber pilots in the Soviet air force during WWII, made nearly 1000% of its Kickstarter goal. Urban Shadows by Andrew Medeiros and Mark Diaz Truman, an urban fantasy game that asks questions about ethnic identity in an attempt to capture the diversity of cities, made well over 1000% of its Kickstarter goal. Avery Mcdaldno’s Monsterhearts, a game about teenage monsters and the complexities of sexuality and queerness, was short-listed for five major gaming awards.

There is also the game Bluebeard’s Bride, which I am currently developing with designers Marissa Kelley and Sarah Richardson in cooperation with Magpie Games. It’s a tabletop horror game based off of the original fairy tale, and it focuses explicitly on the themes of feminine horror and agency, a first of its kind in pen-and-paper. Through the eyes of the Bride and her exploration of Bluebeard’s mansion, which is also her prison and perhaps her doom, the game examines what it means to be a woman in untenable situations. The game is still in the playtesting phase, and has not been officially released yet, but was one of the most popular games at both the Metatopia and Dreamation conventions.

It’s important to point out that sometimes games make an effort towards diversity, fail, and go back to make corrections. This is not only okay, this is great! Game making is an iterative process, and by failing we often learn much more about what works and what doesn’t. For example, in an effort to ensure that How We Came To Live Here engages the culture and myths of the indigenous peoples that inspired the game, the designer Brennan Taylor has temporarily halted sales of the game as he works with Native American consultants to improve it. The Strange was initially criticized for its approach in depicting Native American people and its use of stereotypes, but Monte Cook Games is now working with Native American writers to fix these issue moving forward.

Despite the propensity for leaning on default Western narratives aligned with the white male experience, minority settings and stories are not only accepted, but hungered for, not just in tabletop, but in video game RPGs, too. Video games have been as prone to defaultism as tabletop, yet we are seeing movement here as well. Never Alone by Upper One Games tells Alaskan indigenous stories through its protagonist, the Iñupiaq girl Nuna and her Arctic fox. Never Alone was developed in cooperation with the Cook Inlet Tribal Council, which works with the local native population. It was nominated for several different awards, including South by Southwest’s Cultural Innovation Award and the British Academy of Film and Television Arts’s Best Debut.

Similarly, Lienzo, a Mexican studio is producing a game called Mulaka, which I’m consulting for on the U.S. side of development. Mulaka is an RPG based around the mythology of the Rarámuri, an indigenous people of Chihuahua. The Rarámuri culture has a rich living mythology, but has had almost no exposure outside a handful of dedicated anthropologists. Mulaka is both a vehicle of culture preservation for the Rarámuri, and a way to share their culture with others. Mulaka has garnered a lot of attention from the press, and even interest from the Smithsonian, despite the early stage of the game’s development.

Currently, the greatest interest shown in exploring non-normative narratives in both analogue and digital settings has been by independent gaming companies. In part, this is probably because the larger companies have financial stakes in long-existing franchises and there is a perceived risk in alienating the core audience if a franchise moves away from the status quo. While some companies like Paizo and Wizards of the Coast are changing, progress is slow.

However, you can make a setting for your favorite game, and publishing games has now become easier than ever. Cheap and accessible printing technologies have made the process of publishing far less complicated, and crowdfunding platforms like Indiegogo, Patreon, and Kickstarter provide the capital to get it done. We may be on the cusp of a renaissance in role-playing games, a movement where voices otherwise unheard in gaming now have access to speak through the medium.

The opportunity to release our imagination in new, unexplored avenues through gaming is vital to making the hobby accessible and open to all. When we create games that incorporate minority themes, it signals to underrepresented groups that their stories are valuable and acknowledged and it tells them that they are welcome and wanted in the geek community. It also shines light on powerful and fascinating narratives that would otherwise be hidden away. Minority settings give visibility to huge parts of the world, past and present, that in our media goes largely ignored. And it helps break negative stereotypes by connecting us with the lived experiences of real people. At its best, we can learn about each other through the games we play, building greater communication and empathy into our own lives, and making our worlds all the richer.

Whitney “Strix” Beltrán is a mythology and games scholar as well as a designer, consultant, and advocate in the gaming community. Find out more about her at her website or on Twitter.

Thanks for writing this. It articulates a lot of how I feel.

As a straight, white, male, U.S. game designer, I really value the opportunity to get perspectives that are not my own. As a friend put it once: “You don’t know. Listen.”

I feel lucky to have a voice as smart as Stix’s to listen to. And thanks for the list of games to look into. I’m pretty aware of the tabletop world, but there were a few things I’ve never heard of before that I need to track down.

This is an excellent piece – I’m very glad you put it forward!

I especially like your comments about how games that attempt not to default and stumble while doing it can correct with care and still move forward. The fear of getting things wrong shouldn’t prevent us from trying to do things right.

And I so loved Never Alone!

I remember how important it was for me as I was growing up and forming my identity to see in fiction and games characters who I could identify with; it told me that I too could be the hero, have my own story, not just support a man’s story. I can only shudder when I think how persons of colour are erased from the Western World’s narratives. How could this not hurt to be constantly relegated to scenery and extra? I don’t want to erase otherness and make it conform to my wallpaper. I want to embrace the Other and invite them to star in their own story; I want to listen to that story and enjoy it along with mine and others.

When I realized 20 years ago that the gamers I interacted with always defaulted to white Americans, white Brittons, or pure stereotypes (in that order of descending preference), and all important NPCs were always men, I developed a mental habit of always considering who else could be there: does the merchant, captain of the guard, or scientist have to be a white man? Who else do I see in our world in this position? Who else could be there?

Fantastic article! Eye-opening, articulate, and powerful. Thank you for writing this.

In the context of the gaming world, I really don’t understand this mindset.

— “Without seeing themselves in these stories, why would they participate?”

To me, the whole purpose of role playing is to a) do ANYTHING you want and b) play a role other than your real life. Role playing as yourself would be horribly boring.

It’s the one medium where you don’t rely on creators and publishers to predetermine everything, so it’s the one medium that should be immune to these issues. Failure to role play with diverstity is the fault of the player, not the designer.

Great piece. Definitely amazing that there are so many supports for creating your own work out there right now.

Comment at #6 unpublished, along with direct responses. Please see our Moderation Policy for further information, and keep the discussion civil and be respectful of other commenters, moving forward.

Great piece! As someone who sees representations of himself in mainstream media (whether that’s RDJ or Jon Hamm), I have to pause and reflect to understand that not everyone is in such a privileged position.

Pieces like this help me do that. Thanks.

Theo: Why would anyone want to participate in a hobby that loudly, vociferously, and frequently tells them to go the hell away?

If the power of RPGs is to let someone be something that you can’t be in real life, what’s so radical about saying that white people (frex) should have to play brown people once in a while? Or is that a standard that only works one way?

Thank you for writing this article.

I was very heartened to see Monte Cook Games listen to criticism and take action by actually hiring Native Americans to create better representation in their game, The Strange. I was very impressed by their radio interview on Native Trailblaizers:

http://www.blogtalkradio.com/nativetrailblazers/2015/03/27/native-american-culture-in-gaming–a-conversation-with-monte-cook-games

It’s important to have diverse settings, characters, and perspectives but it is also so important to work with diverse employees and freelancers. So many of these potential issues would be caught early if the people being written about were actually represented on the creative teams.

And change is slowly happening! I have been hugely impressed by the steps towards diversity in characters that both Paizo with Pathfinder and Wizards of the Coast with D&D 5E have been making into reality.

For anyone interested in learning more–how GMs, players, designers, and writers can help–check out the Gaming As Other series: http://www.strixwerks.com/gaming

Thank you Whitney for writing this. Thank you Tor for publishing it.

I find the article interesting, but I’m not so sure I agree with the conclusions. Whitney wrote:

Two points here:

If the setting forces all players to play a minority character, it levels the playing field. That racist cop goes after all of them equally, just like the ogre in hack-and-slash fantasy. By contrast, you can get really eye-opening experiences when you sit around the gaming table with people just like you and the GM treats some of their characters differently. Hello, Mr. NPC, I want to be heard, too. Why are you ignoring me?

And second, these days I buy more RPGs than I play. The way to “punch through defaultism” is to change default games, not to write niche products. Complain if a fantasy game shows only white male warriors, or if the females all wear a chainmail bikini. (Historical settings may have an excuse.) Complain if the far future setting has only white male pilots and the females are confined to sickbay.

Would have liked to have seen an emphasis more on authors, creators, etc. becoming more familiar with minority character types/themes than with

Forcing the minority role into your work is a bit like affirmative action in that you’re doing the right thing, but potentially for the wrong reasons. By allowing yourself to become comfortable and familiar with “non default” ideas, you open the door to the possibility that a broader representation of people and culures becomes natural. Becomes your new default.

I think we’ve seen too many examples of “forced” diversity failing, and failing badly, in literature, gaming, etc.

I’m really glad that people are taking steps to create games that expand the potential of narratives and re-examine what is default in our gaming world. I’m excited to see what other games come out of this.

Thanks for writing this!

@wundergeek

“… what’s so radical about saying that white people (frex)

should have to play brown people once in a while? Or is that a standard

that only works one way?”

I don’t know what you mean by “have to.” It’s a hobby. You can do whatever you want. Or not. There aren’t any rules — or if you follow rule books, there’s nothing that says you can’t change them. Compared to fiction, TV, film, comics or video games, RPGs are by far the most diverse and inclusive medium in the world. (or least diverse, I suppose… it’s up to the player)

Comment #18 (and direct response) unpublished by moderator. Please take a look at our moderation policy and keep the discussion civil. Thanks.

I value games that challenge me this way. “You have to play something outside your experience” is an exciting prompt to get from a game. It’s challenging and it can be daunting, but that’s also invigorating to me. I routinely play people not like me (women, non-white people, people of other species, people of other political beliefs), and having options set before me that push me outside of what I already know about really wakes me up and gets me interested.

I am reminded of Vincent Baker’s Apocalypse World (which Monsterhearts, mentioned in the story, is based on). You choose your character’s gender from a list, and there are more options than “man” and “woman.” By seeing a list that includes things like “transgressing,” “concealed,” etc., people who don’t identify with one of the two big genders get to feel represented by the text of the game. They can choose to take that option, or not. People who feel comfortable in one of the two big genders, on the other hand, have a hand extended to them saying, “Hey, there are lots of different kinds of people. Want to try to play a kind of person you haven’t thought about playing before?” I think that’s a wonderful thing. A win-win. I see no down side.

“I want to embrace the Other and invite them to star in their own story;

I want to listen to that story and enjoy it along with mine and others.”

Here here!

I’m so glad to see this conversation happening productively and broadly. Thanks to Tor for the platform and to Strix for the excellent piece.

@o.m., you bring up an interesting point – how does a game that by its setting limits player characters to only, for example, the roles of oppressed minorities, meaningfully address racism?

I think the answer is that it often doesn’t. As you appear to suggest, giving players a wide choice of characters and then revealing to them in play that only some of those characters are oppressed, while the others are privileged oppressors, could definitely act as a shocking life lesson for the players, and might perhaps incite more personal growth and change.

I imagine the author of this article isn’t exactly making a call for “activist” or “art” games, though. By the examples given, these are all highly enjoyable and entertaining games that simply are serious about representing diversity or a non-defaultist narrative in various ways. As you’re suggesting in your comment, inclusive games and activist games usually employ very different design and result in very different experiences, even when they’re complementary in the social cause that inform that design.

Similarly, writing entertaining games that happen to also be seriously diverse and representative of many different experiences and narratives is not limiting yourself to niche appeal – rather the opposite, as these settings tend to be inclusive to a more diverse player base than a “defaultist” one is! Even if the games mentioned in the article aren’t as popular as the biggest names, they’re commercially successful and critically acclaimed. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that Paizo and WotC has taken steps towards more inclusivity in art and writing in later years as well!

As pointed out in the article, there’s a lot of interesting video games coming out designed by different cultures and creeds that break out of the traditional molds.

I think this is a better vehicle than tabletop games, as you get a lot more out of it with an informed narrator/conductor than having someone with about the same experience with the new culture as you trying to lead the exploration.

@13 Wundergeek

“If the power of RPGs is to let someone be something that you can’t be in real life, what’s so radical about saying that white people (frex) should have to play brown people once in a while? Or is that a standard that only works one way?”

The power of RPGs is to let you be whatever you want to be, and explore anything you want. Your “brown” (?) people, and perhaps those “yellow” people too, could be “white” if they wanted, or they could pick any colour, gender, sex, profession, or anything else they wanted.

The true power of RPGs is choice. I’m glad more options for everyone are becoming available, making it easier for gamers to tell diverse stories and have others participate in them.

For those who are saying “how can you understand oppression when everyone plays one of the oppressed?” — consider Night Witches, where players play female Soviet night bomber pilots and the GM is specificaly directed to hit the players with challenges driven by their gender (as long as everyone at the table is down with it, of course)

This was super interesting for me as the GM because it made me think of sexism across a spectrum from “you get snubbed for decorations” to “the cuter ones amongst you will be swept up to serve as concubines for the local nomenklatura”

When I ran it, I had a local general’s staff dropping off their dress laundry for the women to do. Because they were busy flying at night, they were forced to do the laundry during the day, when they should have been sleeping and recovering from missions. Anyone who refused to do laundry risked a visit from General Igor’s NKVD drinking buddies. The pilots’ fatigue made their night missions all the more dangerous and ineffective but no one in a position of power cared because as far as they were concerned the 588th was just a bunch of uppity ladies flying the least capable planes in the Soviet arsenal.

Theo16 — The mindset isn’t “Without seeing themselves in these stories, why would they participate?” really. It’s more “Without seeing themselves included in these stories, why would they feel welcome enough to try to push their way in?”

When presented with a game that’s wall-to-wall filled with folks who don’t look at all like you, that doesn’t exactly feel like a pool you wanna dive into.

If you’re a white person and have been in the hobby for a while, you’ve had decades of games where 90+% of the people depicted in those games share your skin color. What would those decades have felt like to you if there’d been at best 5%? And what if that percentage reasonably-closely reflected the amount of empowerment you and those like you had in real life? Would you feel welcome by that game, invited to play it?

If your answer to that was “yes”, I gotta say it’d feel pretty disingenuous.

Just a nit here. Assuming the market is USA is amother form of defaults.

Otherwise excellent points. I would add, as a mixed race individual, that having decent heroic representation of non-western-white archetypes would provide a lot to the “default”games, and be a quicker way to punch though.

Great work! But… no love for Nyambe? A published D&D setting based on Africa deserves at least a mention here!

tygervolant, I just love Nyambe! Also Spears of the Dawn, published a couple of years ago and in the same spirit.

@27, as a member of the empowered majority I cannot imagine how it feels to be part of the disempowered minority. I might play one in a game, but I’d always know that back in real life things will look differently. The closest to disempowerment would be being a geek at school, but where I grew up that was socially acceptable.

Regarding those game books, imagine you had a choice — would you want a few of them full of people like you, or would you want all of them with some people like you?

For some science fiction adventures I’ve GMed, I flipped a coin to select the gender of NPCs. For others, I made a distinct effort to get a 50-50 balance. I wouldn’t have dictated the gender of the PCs …

I am of the opinion that, while the practice of “defaultism” is inherently lazy and condemnable, the argument set forth here does not do proper justice to the scope of the issue it is trying to address (lack of minorities participating in, or represented in, RPGs), and brings it out of proportion.

Many fantasy settings, for example, have a large variety of races and cultures to be played. Elves, dwarves, orcs, all have their own heretitages to explore. Certainly, the goal at that point is not to see yourself within that world, but to create a character unlike yourself. Thus, you are already free to explore an identity that is not yours. On the other hand, “Modern” settings also allow the player to create a character of whatever gender or ethnic history they so choose. And once we’ve reached Space games, well, despite what science fiction writers would have us believe, even alien races are not likely to be mono-race, mono-culture. However, for the sake of not filling up the book with dubious amounts of racial distinction and the cultural morays that differ between the same species, at that point it becomes much more simple and effective to condense said species, and thus the same could be said for humanity. They take the most core traits, and leave the rest up to the players.

I find the crux of the issue to be, moreso, that it is hard to adopt a role that exists in the real world, but is alien to you. It’s the same issue with the cries for more diverse characters in the media: if the writer/player isn’t fully educated on the background of the culture they’re portraying, it will come off as a caractature on some level. As not to offend, it is far safer to stick with what is known, rather than make up details based on accounts seen in one’s distant past.

And as such, it is my opinion that applying the issue of “lack of diversity” into most roleplaying environments is a falicious judgement. In review:

1 The intent of most settings is already to be a character that which you are not.

1.A The background of the player is rendered irrelevent by the nature of the medium and the genre chosen.

1.A.a As their background is irrelevent, and as most tabletop settings are diverse by their own nature, it is foolish to “look for people like yourself” in a game, as any relations will only be small surface details.

2 Attempting to portray something that exists, which you are not a part of, will most often lead to a display of the most visible details, rather than providing any deeper perspective.

2.A The player is not held back from exploring in any way by the games themselves, but by society, culture, and human nature.

2.A.a If it is the creator’s goal to create a game to simulate a culture that exists/ed, and the player is to be limited to it for the sake of a learning experiences, it is up to the producer to make an engaging, factual, and mechanically demonstrational product, and should be judged seperately from games entailing fictional worlds.

2.A.b If the creator’s goal is to simulate something that does not exist, they are free to do so in as demonstrational and detailed way as they desire, in alignment with their intent in creating the game, as to not overclutter their books with details that are not relevent to that world as presented, or muddle the mechanics of the game.

As such, I would like to see a sociological study of this claim that people of minorities feel barred from engaging in tabletop RPGs because of their race or gender, and what they feel it stems from. Personally, it sounds to be putting words in their mouths. Further, it likely does not paint the full picture as to why they do not engage. Simply, it is an assumption. Not that I’m asking the author of this article to prove the statement with such evidence, it’s just a critique of something stated as if it were factual and common knowledge.

Defaultism is an issue in American society and media, I will not attempt to argue that. However, as an avid tabletop gamer, I do not appreciate seeing critiques made against the medium on faulty premises. Seeing that you yourself are engaged in the field, I’m sure you can see where I’m coming from on this.

As a personal note, I find that if we tackle our American and Urban fear of other people, it will be far easier for us to intigrate the perspectives of people who are different from us, rather than through any sort of measure that encourages inclusivity. However, that is only tangently related.

Thank you for your article, and I hope my critique of your arguement is met with reasoned debate from both you and my fellows.

Great article! Even George RR Martin (Song of Fire and Ice/Game of Thrones), for all his awesomess in creating Westoros, falls into stereotypes when he writes of the near-eastern lands. The intrigue and grey morality of the real-life War of the Roses is apparent between the great houses of the west. But all you really see in the east is the whitest person in Westeros saving the desert people from themselves in a continuation of manifest destiny/white man’s burden. Even a hint of a character like the real-world Baibars (the slave who overthrew his master, installed a female sultan to rule, then founded the dynasty that inflicted the first defeat upon the Mongols and drove the crusaders from his land) is absent.

@fred Hicks:

“When presented with a game that’s wall-to-wall filled with folks who

don’t look at all like you, that doesn’t exactly feel like a pool you

wanna dive into.:”

Again, I have to ask, why does it matter? Who cares what the default characters look like in a game? If you don’t like what’s presented to you in a movie or a video game you have no recourse. In a pen&paper game you can change it any way you want. All it takes is imagination, which most gamers have a ton of. You can play with or as anyone you want.

If the problem is actually that the PLAYERS won’t let other people in, or won’t let them play any character type the want, then the solution is just to find better people to play with. And by the way, EVERYONE has problems or issues with other people from time to time, particularly in a creative atmosphere. It usually has nothing to do with race or gender. I don’t know why it’s suddenly important to act like minority players can’t deal with it the way anyone else does — you either leave or work towards making it better. It’s hard, but dealing with personality clashes is hard in any part of life. Occasionally everyone feels unwelcome or has some sort of barrier to entry with a particular group. You deal with it and move on — it’s not worth all this hand-wringing.

I’ll speak from a personal perspective, but where I grew up (80s NYC, 90s DC) no one thought this was an issue. I can’t remember a gaming group (D&D at first, then Gamma World, Top Secret, Star Frontiers, Star Trek, Star Wars, Heroes Unlimited, Robotech) that was all white or all male. No one gave a damn. And the character types had as much variety as our imagination would support.

@@@@@ 32. Linder: Representation matters. There is no silver-bullet solution to the problem. Rather, the problem is solved by an array of people making small changes that make the hobby feel more open to people who aren’t straight white cis men.

As far as the question of whether it’s worth it to try and risk offense, Strix already addressed this in her column and advocated taking a risk and being willing to admit and correct when you make a mistake.

I think you’re claiming too much knowledge over why people play fantasy games or produce and use fantasy settings. It’s not all about playing someone you’re not like. Sometimes it’s about playing someone you’re like, but in a situation unlike those you’ve faced. Sometimes it’s about playing parts of yourself and parts of other people. I’d also argue that if you’re doing any character work beyond thinking of your PC as a toon with fighting powers, you’re going to be in some way exploring something about yourself or about how you react to aspects of others’ personalities.

Have you been represented in RPG writing as ubiquitously as I have, Linder? Because if so, maybe that explains why you don’t see this as a problem. And if not, you would be the first person in that position who that’s been true for in my experience (that I can recall anyway).

@@@@@ 34. Theo16:

“Who cares what the default characters look like in a game?”

Many people, including the writer of this article and most of the people commenting on it.

Yes, you can use your imagination to change things presented to you in a game. You could also make up the whole game and have no rules. But instead, game designers present options and things they are interested in seeing get explored. In some games you must play religious vigilantes. In some games you must play women fighter pilots. In some games you must play pansexual, polyamorous, prehensile-toed, multiple-PhD-having starfarerers. Could you make up your mind to play those characters? Sure. But if the game presents that as your only option that’s called creative constraint. And creativity flourishes under constraint.

The designers of games that want to fore-front non-white, non-male, non-straight, and trans* experiences are merely doing what game designers have always done. Presenting options that they think are interesting. Why this is objectionable is beyond me to a frustrating degree.

This article is not addressing behavior at the table, so I don’t know why you’re bringing it up.

Have you been represented in RPG writing as ubiquitously as I have, Theo16? Because if so, maybe that explains why you don’t see this as a problem. And if not, you would be the first person (possibly second, depending on what Linder says) in that position who that’s been true for in my experience (that I can recall anyway).

To the article writer:

Good to know that your projects and the projects you like are going so well, with funding and so on. And I did not know the history behind Tulsa, very interesting, and could be used on an RPG game.

But my impression from the last years of tabletop RPG community was that it was becoming more and more a market where companies mattered less than consumers. My experience, from the mid-90s so far, has been that the good old RPG book, box and magazine is becoming less needed with time, and what RPG gamers consume is found more on the internet.

My last 2 campaigns (including one that is on-going) were made using free RPG systems that can be found on the internet (Fuzion and FATE). The last RPG book I bought was purchased on Lulu, a print on demand service. For the last decade, I have bought more pdf RPG books than old-style RPG books. And I’ve abandoned RPG magazines for RPG blogs, that give tips on gamemastering and so on.

My experience might not mean much (it might be vastly different from other people and most of the market in the US or Europe), but it shows that what it takes for making a RPG product is not much (basically your own blog, or a word processor and PDF converter). So I don’t know why the obsession on what’s being published, rather than what’s being played. Because what’s being published is becoming a smaller and smaller share of what’s being played.

People were never actually required to play on the published RPG settings, which only gave ideas for the GM to use, but nowadays, it seems to me, less and less people are actually playing in any official RPG setting (this might have to do with end of meta-plot in WoD, WotC no longer supporting most settings and the edition wars).

So, if people are not playing as minorities in RPG sessions (and I don’t know how true that is), that’s more a problem of the gamers than the game designers. The same can be said of welcoming people of different background in their sessions (also don’t know how true that is as well).

P.S. I’m not white, nor part of the majority race in my country. Never felt that the stories that were told in RPG sessions specifically excluded me. Also, most of the time I was the GM.

@@@@@robertbohl

“Have you been represented in RPG writing as ubiquitously as I have,

Theo16? Because if so, maybe that explains why you don’t see this as a

problem.”

No, there are no games I’m aware of about overweight technical writers with two kids. Thankfully they are much more imaginative than that.

Honestly, I have never recognized myself in the rulebook, genre, NPCs or setting of a game I’ve played. I don’t really care to, either.

Yes, you can do it on your own. Being given the option prompts you to take it. That’s the whole thesis of the post (the way I read it). Why do people keep saying, “I don’t need it, I can do it on my own?” when the whole point of the article is that, yes, you can, but that there’s demonstrated value in putting the option in people’s hands?

@Linder, Theo16 and others, quite a lot of roleplaying characters, especially for people new to the hobby, are like the player but with special powers. Like me, only an dwarven fighter. Like me, only a space pilot. It takes gaming experience to step back from yourself and imagine the choices of another. A character who believes in the divine right of kings. A character who doesn’t care if the business partner has white skin or blue skin or green and scaly skin.

So all other things being equal, it would be nice if all gamers could find representations of people much like themselves in the book. I wrote all other things being equal because this opportunity should not detract from the historical accuracy of historical games. In a fantasy or future gamebook, it can be done, so it should be done.

Another thing is that every published author is shaping our common culture, a little bit at a time. If you believe in diversity, represent it in your work as normalcy. If enough people do the same, it becomes the new normalcy.

But does it? That’s the point I’m making here. And really, if you want to make the hobby feel more open, I’d suggest you highight and not simply ignore the minorities already playing the games. One of my players is a black female, another a closet unchanged transgender. Meanwhile, Theo mentioned that he has never had a game that did not include someone different from himself. To simply assume that these people aren’t playing games, and then to further assume it’s because creators haven’t reflected their personal background in-setting, is a slight leap. If anything, it’s the same sort of Defaultism that the author is speaking out against.

Except, this is more than simply risking offense. One is demonstrating specifically how little they know about that culture when they attempt to portray it, either falling short and ending up with ‘a character with a coat of paint on them’, or going too far and presenting an ethnic caricature. And this kind of mistake is not easily recognizable. If me and my group had never seen a black urban youth in person, and I attempted to play one, I would be perpetuating stereotypes I had picked up from other media, and no one would be any the wiser.

The key point here is that the player is given the opprotunity to not be themselves. In your games, how many players have defaulted to playing “Me+”, as opposed to taking on a role that is different from their own in some way? To simply cut this short at ethnic portrayal does the medium no justice. A Fighter will have different attitudes from a Mage, same for a Navigator and a Diplomat, or an Accountant and a Park Ranger. In many games, the point is just as much (if not moreso) where your character is going, as who they’ve been.

Getting back to your point, however, I don’t wish to devalue these informative games. In fact, I find the best games are designed with a specific mood or theme in mind, with an engine built to best reflect it. Don’t Rest Your Head, or the independantly produced “suffering magical girl” game Magical Burst are both good examples of this. And indeed, I come to DRYH to play someone whose life is falling apart, or MB to pretend to be a little girl with powers that far outstrip her self control or common sense.

However, I find it foolish to hold games whose intent is to provide a broad experience to the standard of needing to provide ‘visibly diverse options’, especially when the characters (by the merit of the setting) have a very different culture from our own. Not to mention, this is also a very hard to approach topic. If Wood Elves and Underground Elves have radically different natural dispositions (stat changes, skill bonuses, abilities), why shouldn’t a White Human have a different set of dispositions from a Black Human? They’re from different parts of the globe. Because that would be racist, and we cannot have that. And yet, if Elves can have different stats by their ethnicity, is that not promoting discriminatory practices as well? The whole thing is a mess.

Regardless of the above, my point is that the as the games do allow for the diverse experience, and often provide incentives along much of the spectrum of identity, that a lack of representation is not the issue here, as no one is being represented in these games. There is no Polish, no Irish, no Slavic, no American; why should there be an Arab, a Malaysian, or a Chinese? So yes, let us please have more physically diverse art. But let’s not try to make any sort of enforcements of such in any case of which the intent is not to accurately simulate Earthly humanity in the first place.

Returning to your point of the diversity of reasons that people play, the optimal experience only comes when everyone is on the same page. Just as someone building an Action Hero is going to be disruptive to a Horror game, someone trying to be Me+ will hamper the party of gleeful psychopaths that tend to be adventurers. On the other hand, if the cast wishs to explore themselves in a fantasy environment, one person choosing to roll a murderhobo will throw off the game entirely. And here is the value of these teaching games, these settings designed to provide a different environment: they were built with a certain kind of experience in mind, and they intend to provide it.

This is where I take the most issue. I understand that it is intended to be an honest question as to my gender, sexuality, and race, to try to lend credit towards my argument against an inherint need for diverse representation. However, it comes off to me as much the opposite, an attempt to disqualify my arguments as ignorance of the issue. To which, I must reply that the standard cuts both ways. You admitted to being Straight White Cis Male much earlier, and thus I must ask: are you qualified to make the judgement as to why minorities do or do not participate in the tabletop scene? How can you speak for minority groups, saying that they do feel left out simply because they are not depicted? I am of the same cloth as you, here, and thus I believe that standard leaves us at the impass that neither of us are actually able to speak to this issue to any legitimacy. However, you are a gamer. I am a gamer. We are both qualified to speak of our observations (rather than our assumptions), and what we think would and would not work, and as to what we think design priorities should be. And I am saying that this entire conversation NEEDS to be split up into the following catagories, as to not start filing square pegs for round holes:

1. “games that simulate humanity”: should strive to include as many ethnic groups as possible.

2. “games that include humanity, but don’t intend to fully simulate its nuances”: should be under no obligation to include diverse humans, and are free to set their standard of ‘average’ at any distinctions, whether they happen to exist or not.

3. “games designed to provide a certain experience”: should be as diverse or as ethnically focused as fits the experience they intend to provide.

My point simply being, we have too many White people simply assuming that they know the factors that discourage other ethnic groups from participating in games, and too many well meaning ideologes not acknowledging their presence at all. However, given that I have a background of study in Sociology, I find that this question is far underexamined, and that people are jumping to conclusions and oversimplifying the issue. They are ignoring things like language barriers, ethnic cultural bubbles, internal cultural behavioral standards (Black people not allowing themselves to be seen as ‘acting White’, for example), and the media’s tendancy to portray gamers of all sorts as pasty white dudes. And as such, the people pushing this issue can easily be doing more harm than good, especially in assuming that those challenging specific efforts to bring various people into the scene must have some sort of agenda of exclusion.

This is a job for social scientists (who despite possibly being

Straight White Cis Males, are more qualified to examine the topic than laymen) and for the minorities themselves (who are not being barred enterance, thus the responsibility of joining the hobby falls upon them and their social ties).

Thank you for your thoughts.

@@@@@ 43. Linder

Who is ignoring the minorities already playing games? No one is doing that. The article, to me, isn’t saying “No minorities are playing,” but, “Here’s a possible way that we might attract more minority* people to the hobby.” No one’s being ignored. Strix (and many others of us) would just prefer if more people felt welcome.

I don’t see how what you’ve described is more than risking offense.

“The key point here is that the player is given the opprotunity to not be themselves. In your games, how many players have defaulted to playing “Me+”, as opposed to taking on a role that is different from their own in some way?”

I can’t tell you how many there have been. I know I have had lots of different reasons for playing characters, as have other people. My point is that you’re making a blanket claim that people play fantasy to play someone unlike them, and that’s not always the case, or if it is, it’s not always 100% the case.

You can’t claim “lack of representation is not the issue here” as though anyone is saying lack of representation is the only issue. Lack of representation is an issue, and this article is in part talking about how to rectify that. What you’re doing is the equivalent of asking people at an anti-war rally why they’re not rallying about economic justice. Both are valuable things to talk about, but it’s a change of topic.

What kind of “enforcements” are you talking about? Games where you can only play a woman, or a non-white person, or something? I don’t see any force on display here. What I see is someone saying, “Hey, try this!”

I would disagree that the optimal experience only comes when everyone is on the same page. That’s impossible. People are going to be varying in their attention to various parts of the game. Yes, you need enough coordination of thought to create a shared imagined space and work through the details of what’s happened in the narrative, but people don’t need to be in lockstep. People can be exploring different character options for different reasons.

My question about how often you see yourself … that’s literally the question I’m asking. Because as someone who sees people like him constantly in media, it took me shutting up and listening to people who weren’t getting that, listening to how it made them feel excluded and devalued, to appreciate that it happens. And to appreciate the value of efforts being made to include them. So if no one had done that for you I couldn’t blame you for not getting it. And it seems like you don’t get it.

Games that don’t intend to simulate humanity’s nuances are games that aren’t interesting to me. But I don’t understand why you’re bringing them up. Strix has suggested that there is a way to design and write and produce games that might be of value. That’s all.

I don’t make any judgments about why anyone does anything. I’m not speaking for anyone. I just listen and repeat what I heard. And I believe I’ve been very careful to craft my words accordingly.

And the person who wrote this article isn’t speaking from the ignorant position I am. I’m basically just nodding along at what she said and elaborating as I understand it.

* I’m uncomfortable with using the word “minority,” especially because this is a global audience so in some cases (non-whiteness, being a woman), it’s inaccurate. But I take Strix’s article to be referring to the US and not the entire world (with obvious applications outside the US).

@46. robertbohl, and the author.

I would like to apologize for my having brought what I see to be legitimate arguements and critiques to what is nevertheless the wrong discussion for them. I do oppose your analogy of my points to that of someone bringing an incredibly tangantal topic to an anti-war protest (and in fact, am insulted by it), seeing as I have been far closer to the ball park than that. Further, I do hold that I made points that do need to be said about the broader issue of the perceptions people have of this hobby in general.

However, I agree that this is not the proper context for them, and will be thusly retracting myself from the conversation. I apologize again, for having wasted your time.

I’m rather dismayed by the brick wall conversation. @Linder, Theo16 and others who “find it foolish to hold games whose intent is to provide a broad experience to the standard of needing to provide ‘visibly diverse options'” and who think everyone should power through whatever character representation is offered regardless of what they look like: it’s not sufficient to be able to do that.

What we’re talking about is emotional: “Am I welcome here? Am I considered even part of the audience? Because if it’s targeted at someone else, if I’m made to feel grudgingly tolerated, why would I spend my time and effort in this setting/hobby when I have other options?” This may appear a low barrier to you, but clearly it’s there, clearly it has a far-reaching effect, discouraging vast swaths of people from even looking any further at an excellent hobby that could bring them great fun — and also depriving the hobby of their insight and contribution, making it even more of a monoculture.

Henry Ford once told us that “Any customer can have a car painted any colour that he wants so long as it is black,” because at the time that’s all Ford offered. We want to move away from a hobby where one can play any kind of fantasy adventurer, so long as they’re white. (Yes, that’s a quip and therefore an oversimplification, but it’s still too true.)

@sophie: Eexcept in your Ford analogy if Ford is the RPG producing industries & cars are the RPG’s the industry creates, then the cars already come in literally every colour that has ever existed, before moving in to non visible light spectrum & then continuing right on into inventing completely ficitonal colours…. And also the cars are also hover crafts, long boats, flying suits of high-tech armour & the occasional winged horse.

This article is complaining about not having a thing that RPG’s have ALWAYS had.

RPG’s have always offered more than the rather thin excuse for the RPG industry which the author would have us believe exists. An D&D more than most, what with it having the two most prolificly written in settings in RPG publishing history has done a lot with different cultures, ethnicities & other sundry issues.

Heck this isn’t even a recent thing, this has pretty much been the case since the 80’s when D&D became popular. An thats just D&D, if you add in all the other RPG’s out there the amount of different views that are presented just becomes an embarassement of riches.

@@@@@ 51 The Rational Geek

Yes, anyone can do anything. We can sit in the back yard and just tell stories. Giving people an option that they might not otherwise consider is valuable. That’s what the whole post is about. I don’t understand how you can read this and not see that. I literally cannot understand what you’re objecting to.

So I remember a Role Playing system called GURPS, which my friends and I loved because it allowed us to customize our role playing to exactly how we wanted it to be. We also latched on to a game called Phoenix Command (and its cousin Living Steel) because it allowed us to do the same, but in a more modern combat-orieneted environment.

We built amazing, custom worlds completely divorced of any influence than the ones we invited in. Tolkein, Gibson and Lucas all visited our world, but it was our world.

The framework exists today for anyone to create any world, populate it any way, and tell any story they so choose with few barriers. The ability to communicate with like-minded people literally across the globe and play via email, skype, or in a dark shag-carpeted basement around a cheeto-crusted table like our forefathers did.

I guess what I’m saying is that my pushback, and maybe some of others, is against the idea that the tools aren’t there. Everything needed is there, multiple times over. I’m talking right down to the sriracha-flavoured crud to properly pollute themselves gamer-style!

What might be missing is the open invitation from gamers to their friends that might not normally feel welcome at the table, and if present not given the encouragement to play any way they like. That I could see exploring as a topic and seeing how we can improve that.

We’ve already laid a framework for that dialogue from when women were a lot less welcome than today. What has that journey taught us that can be applied here?

@@@@@ 53 swgregory

I don’t see Strix saying the tools aren’t there, it looks to me like she’s just advocating for their increased visibility and use.

@54 RobertBohl

You’re right, but the comments section seems to be getting stuck on the ability question instead of the inclination.

The ability is clearly there, so how do we raise the inclination of those already “in” the community to enrich their own world by more-actively inviting in different views.

I would recommend exactly what Strix does in the article: Games where non-empowered voices in US society are a central (or required) part of play.

We shouldn’t use the term “race riot” like a mantra, with no immediate indication of who, why, when, etc. I suspect most people react to the words based on their limited experience and/or lack of awareness of the history of race relations in this country. I realize “white riot” or “black riot” might be a bit too much, but some indication is useful. Consider:

When the white mayor of a town in 1903, and another in 2003, say: “I don’t want no black people in my town ’cause I don’t want no riot,” we should be aware that “riot” in 1903, and in 2003, likely means two different things.

(Sometimes my prose gets tongue-tied, sorry.)

Stop appropriating my culture. Native American culture is not here to be entertainment for the white man. You think you have a right to ‘stand up for those poor minorities’ when you do not even understand what happened to us. Representing us in your white entertainment is not honoring the tragedy my people have had to suffer through.

I say this politely because I hope it will help you understand. This is not what we want.

Just to throw another resource on the pile, there’s a fun setting for the QAGS game system called “Herland: Perfect Genetic Utopia” where the characters are all female. I also like how the QAGS books always refer to the GM as “she” by default. As a female gamer, little touches like that help a lot.

Great article. I would love to see more focus on this in the community at large.

I can’t help but wonder to what extent the author or the commentors of this article have really played any roleplaying games. Complaining about diversity in the cast of a TV show, movie or what video game characters look like is one thing, as the consumer of such media you often have little choice, but roleplaying games?

First of all, just about every roleplaying game has an introductory chapter about what a roleplaying game is. Let me quote some parts from Vampire the masquerade which happened to be using as my mousemat in the sofa while reading this.

“The book you hold is the core rulebook of Vampire: The Masquerade, a storytelling game from White Wolf Publishing.

…

In a storytelling game, players create characters using the rules in this book, then take those characters through dramas and adventures, called (appropriately enough) stories. Stories are told through a combination of the wishes of the players and the directives of the Storyteller.

…

Whenever the rules and story conflict, the story wins. Use the rules, only as much – or preferably as little – as you need to tell the thrilling stories of terror, action and romance.

…

The story teller invents the drama through which the players direct their characters, creating plots and conflicts from her imagination.

…

The Storyteller the salient details of the story setting – the bars, nightclubs businesses and other institutions the characters frequent.”

So in short, you can create ANY characters you want and tell ANY stories you want. If anything in the book conflicts with the story you want to tell, the story takes precedence, and they spend a chapter of the book to point out this crucial difference between roleplaying games and other games. Roleplaying games are not what is limiting you from a diverse playing experience, any failing in that area derives from the group you play with.

Not even if you only ever play things from a campaign book are roleplaying games not diverse. Starting with the world of darkness as a perfect example they draw inspirations from all cultures around the world to create material.

You want to tell stories focused on African mythology? There is support for that. Are you more interested in eastern mythology? There is support for that. This goes for most roleplaying games with an expansive universe.

So roleplaying game publishers make a point to tell all new players that they are the arbiters of what stories they tell, they also produce material to inspire players to explore a wide variety of cultures, real and fictional.

The starting point of this article is either ill informed or dishonest. Roleplaying games encourage players to and have themselves been been a diverse medium for decades.

Pontus von Geijer

vongeijerpontus@gmail.com

an avid roleplayer for two

decades and counting…

It is not possible to create a more diverse type of game than roleplaying games. The entire Point of a roleplaying game is that you create the story you want to tell. Every roleplaying game starts with a chapter that tells the players that story > rules.

If the players do not agree with something in the game, they are encouraged to change it. You are free to create and explore any character you want, and the storyteller can use any setting, fictional or real, elements from any time or place in history. This is what the game encourages you to do.

Even if one only ever plays Campaign material printed by the Publisher there is a plethora of diversity to draw from. White wolves games alone provide ample material in both support/inspiration for character creation actual Campaigns/stories to play and lore to build your own, all of it drawn from all over the World, based on a wide variety of mythology, and cultures.

It is only possible to Think roleplaying games are not diverse by not looking very hard at what there is available, not Reading the first chapter of any story book, and by not trying to bring diversity into your group.